I was born in Saigon Vietnam to Danish/Norwegian parents early in 1960.

After a spell in Angola, my father had been sent out to SE Asia by the Danish East Asiatic Trading Company (ØK) in 1956 and acquired the heavily decorated brown camphor wood

chest then as a way of protecting business documents from the bugs (Camphor deters bugs).

In 1958 my parents honeymoon trip was the passage out to Saigon on the ØK company freighter.

Then, the only thing that stuck up out of the jungle canopy, the only thing that indicated the city below, was the spire of Saigon’s cathedral.

Nowadays the heights of the skyscrapers in Ho Chi Minh City rival other Asian super-cities.

By the end of 1960 it was getting a little too ‘hot’ in Saigon for a young family and my father was transferred by ØK to Phom Phen in Cambodia.

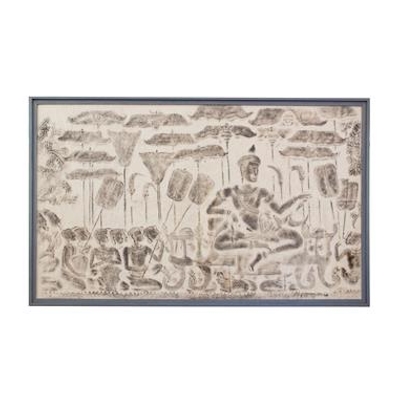

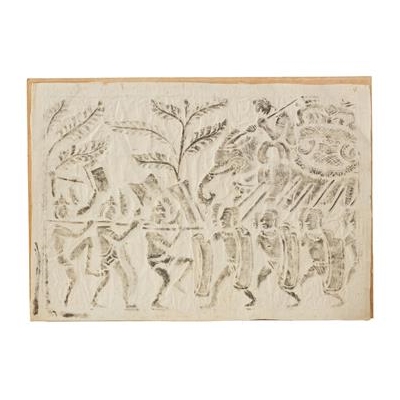

My parents were keen explorers and having driven all over southern Vietnam in a Citroen Black Maria and later a VW camper bus, drove up to Ankor Wat and explored what was then a

largely unknown and unvisited ruin. The first article about the ruins appeared in National Geographic in 1961 – I still have the family copy.

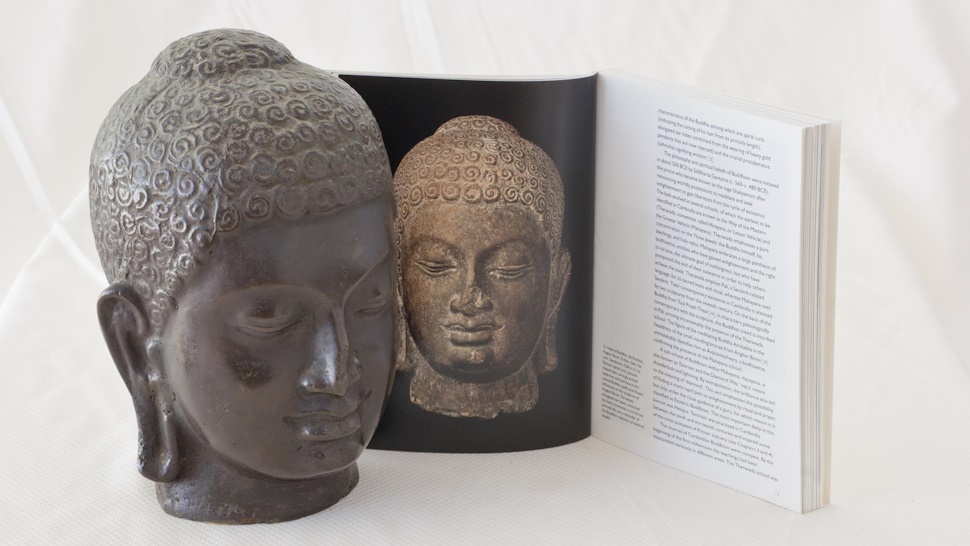

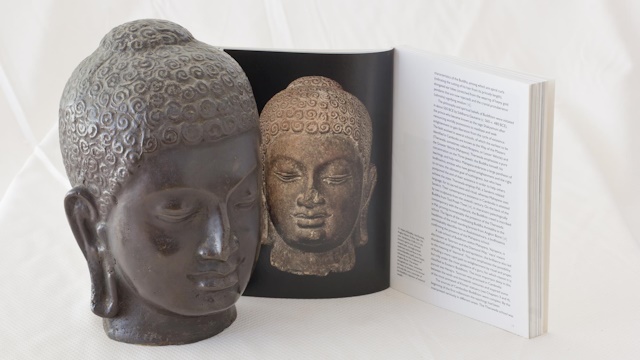

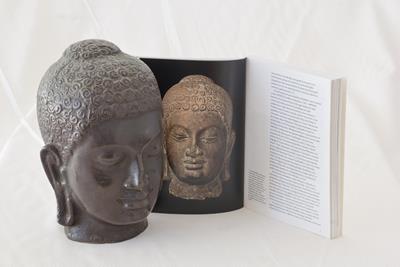

The stone rubbings and the buddha head came from there – they were offered for sale and my parents bought them. They have been in my childhood home since then.

The Buddha head is clearly a copy of the stone original which appears on the cover of Helen Ibbitson Jessup’s “Art & Architecture of Cambodia” (2010) – they are almost identical,

except the nose has been repaired a bit – a nose job!

My parents loved Cambodia and the Cambodians, even became close friends with the Cambodian royal family – indeed Prince Sihanouk was so often in my family home that I knew him as

‘Snooky’.

Whenever my mother went to the market, she always stopped by an antique shop where she admired the statuette. The shop owner explained that it was not for sale as it was the

original and that they were taking copies off it - if she wanted one. She declined but continued to admire it on a weekly basis during the 2 ½ years we lived in Phom Phen.

Some of my earliest memories are of elephants’ snouts snuffling along our first-floor balcony balustrade for the peanuts we left out as treats for them, chasing the gibbons back

up into the plane trees.

When the time came to leave Cambodia in 1963, the shop owner presented the statuette to my mother, with all his family present in a surprise ‘mini-ceremony’ in front of his shop.

My mother was astonished and very touched by the gesture. It wasn’t until much later that she wondered if perhaps the royal family had had a hand in the ‘presentation’ as a way

of thanking my parents. They certainly carried Cambodia in their hearts forever.

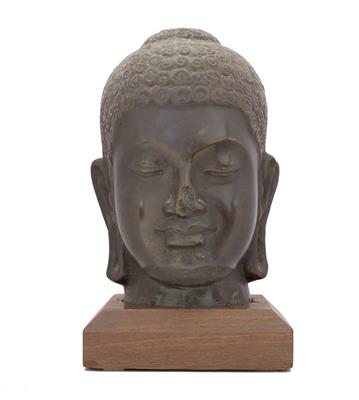

The 47.5 cm high statuette is a cast bronze – the style is of a pre-Buddhist Shiva which indicates it pre-dates Ankor Wat and even the Cham dynasties that were the pre-Khmer,

pre-Ankor rulers of Cambodia. I believe it to be from the 15th century.

The black-lacquered chest is not antique – it was made in Hong Kong for my father in 1965 in camphor wood. Nonetheless it is an impressive piece.

After Hong Kong we lived in Tokyo where my mother studied pottery with a Japanese master. She acquired the sake-warming, conical ‘bottles’ convinced they were ancient. Christies

disagreed while admitting they aren’t experts. I’m not an expert but I have more faith in my mother’s knowledge than Christies. I can provide the letter from Christies but you

need to talk to me not to them. I lived for a short time with a Japanese farming family where these type of conical bottles were still used in the Hibachi under the table.

Throughout the centuries kimono patterns have had huge significance in Japanese culture – as an expression of art, as an expression of status. They were once made of the bark of

the .... tree sewn together with hair. I suspect horsehair but human hair is also very strong and perhaps more plentiful. Perhaps it was a duty to shed for the sewing of a family

heirloom. Two are mounted in strong, glass-covered frames. Four details patterns with ink splashes still intact are displayed. There is another roll of at least two more patterns

that I decline to unroll as it may damage them. Some expert will know how. I’ll include them in the sale of the above patterns, framed and unframed.

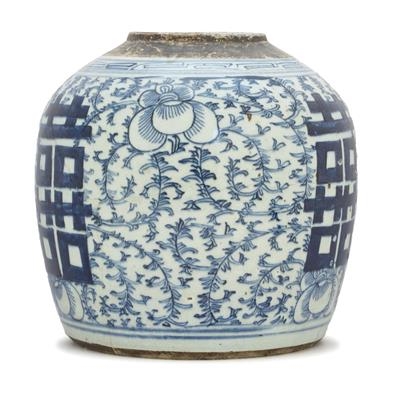

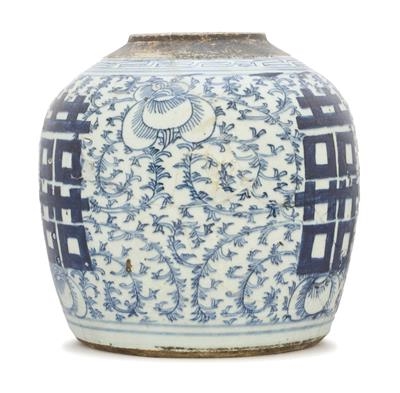

The Ming vase is a bit of a family joke, really. My father picked it up in the Cholon market in their first week in Saigon thinking to make a lamp out of it. He carefully drilled

a hole, inserted a wire and my mother organised a shade. The shade changed colour a few times while the vase never really drew comment until one night at a party in Spain some

expert said ‘you do know that is a Ming vase, don’t you?’ My father said he had no idea and promptly dropped it on the floor, shattering it into a thousand pieces. It has since

been meticulously glued back together – from a short distance away it is still perfect. Up close it is a testament to patience. For thirty years they thought it was junk. The

minute it became valuable, they lost it. What can you say?

All these items are for sale – either as a single lot or individually.